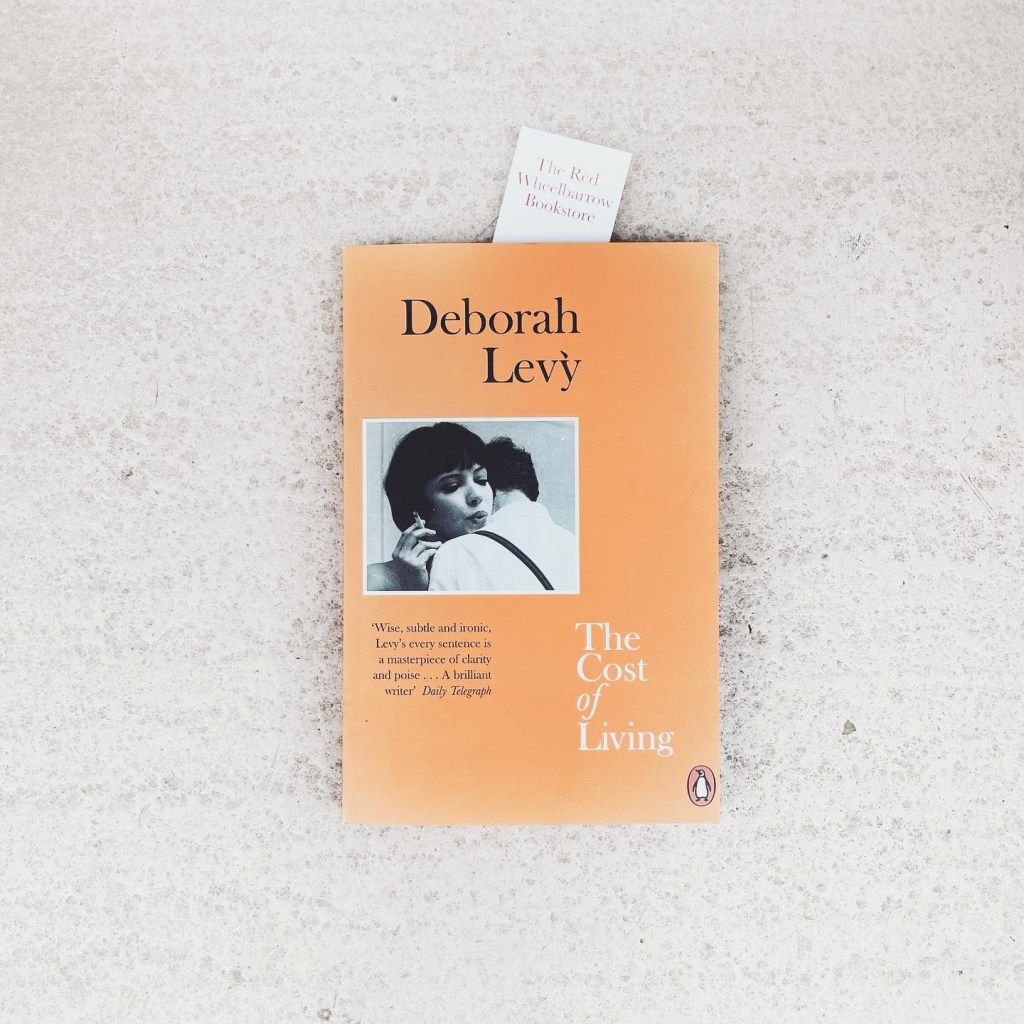

A few days before embarking on my plane trip to my new dwelling across the Atlantic, I visited Penelope at my favourite bookstore in Paris, The Red Wheelbarrow . I asked her what my “last title” should be. She recommended this, the second installment of Deborah’s Levy “living autobiography”. I asked if I should not start with the first volume instead, but she insisted “no this is the one worth reading”. And so I added the bright orangep tome to my bag — a bag already heavy with my son’s growing Pip and Posy collection, planning to read it on the plane. But then the journey’s rocky start meant I did not feel like reading for some time. It took me three weeks to finally reach the conclusion of this slim book.

“As Orson Welles told us, if we want a happy ending, it depends on where we stop the story.”

But, as I neared the end of this other journey, I sent a text to Penelope : ” Thank you for recommending The Cost of Living, it’s wonderful. I enjoy following Levy’s train of thoughts. From the most peculiar observations, she draws the most penetrating insight. And I love her writing, so light it is almost flighty, but then the meaning dawns on you and it is heavy, and full of poetry.” I hold onto these first impressions as I assume they best capture the rush of emotions I felt when reading (and because I am quite proud of the way I expressed it tbh). I was still full of all the feelings I experienced in these last pages. A sort of illumination, as if, by following Levy’s recollection, I had pierced some old, important mystery, or arrived at home, finally.

“So, when I was next in the company of the man who never looked at his wife, I in turn began to look at him never looking at her – at the dining table for example, or in the car, or wherever it was he never looked at her. I wondered what his lack of looking was supposed to communicate. […] on balance, I thought he was clearly telling her that she did not exist for him. It was an odd twist on the Medusa myth, and other myths, too. His eyes, which he had plucked out like Oedipus, were staring at her any way. All the time. He was trying to see her off. It was nothing less than attempted murder.”

Reading her felt melancholy and somewhat lonely. She gave the impression of navigating in a mist, stumbling to find her way. And indeed, that is what she recounts doing : navigating the end of her marriage, the loss of her mother, and uncertainty. She writes about what it is to be a woman, and how tricky it is to try to be the major character of our own life, living the role we choose and not the mask put on our face. She argues that sometimes we have to leave the comfort of the boat and wade into the dark waters, even if we risk drowning in this ocean of freedom.

“If she had left these vital shoes in their hotel room, did she have a spare pair of medical shoes? It felt intrusive to ask him to elaborate on his wife’s feet, but he did volunteer that ‘without these particular medical shoes, he could not hear her footsteps in the house’. […] Now that she was wearing lighter shoes it was hard for him to follow her movement, which he said, ‘was a bit nerve-racking.’

I asked if he was nervous that she would fall?

No, her balance was stable. In tact the lighter shoes were her preference but he felt urgently compelled to retrieve the medical shoes from Paris so he could hear her footsteps in the house.

He seemed obsessed with footsteps. I wondered if his wife had chosen to leave her shoes in Paris to avoid her husband knowing where she was at all times.

Certainly, if there were migrants clinging to the roof of the train, they too were making a bid to slip away. It would seem that he had given himself the job of making sure no one slipped away on his watch.”

On her path to self actualisation, Levy picks on various ideas and themes, unveiling hidden trails. Her insight is piercing, she puts together the scattered clues that reveal our inner turmoils. And this is the light I found in her book. No definite answer, no comforting life lessons. But the ever renewed revelation that this is what writing is about. Or at least what reading is about for me : delicate words that shed light on parts of this meandering trail we call life, poetry that opens doors into the heart. As I enjoyed the airy quality of her writing, the subtle similes; I also savoured the ring of truth, the recognition that new folds of the human experience had been laid bare for me.

“I was half listening and then I was completely listening. Her words opened a space, a wide-open space inside me. ‘I crossed the border alone, I came feeling the black and bluish darkness, the howling of the coyotes, the sound of the plants.’When a woman has to find a new way of living and breaks from the societal story that has erased her name, she is expected to be viciously self-hating, crazed with suffering, tearful with remorse. These are the jewels reserved for her in the patriarchy’s crown, always there for the taking. There are plenty of tears, but it is better to walk through the black and bluish darkness than reach for those worthless jewels.”